By Nikki Babri

While the Harlem Renaissance is now regarded as a transformative and immensely influential period in American cultural history, it wasn't always afforded this recognition. For decades, the contributions of Black artists, writers and intellectuals during this vibrant era were marginalized in mainstream narratives of art and literature. The Harlem Renaissance represents a profound shift in the international cultural landscape, serving as a catalyst for social and artistic movements that continue to reverberate today.

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” a groundbreaking exhibition set to debut in February 2024 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, marks the first comprehensive art museum survey of the time period in New York City in over 35 years. The landmark exhibition will explore the Harlem Renaissance’s profound influence on the development of international modern art.

Bridget R. Cooks, UCI Chancellor’s Fellow and professor of African American studies and art history, is a renowned scholar and curator specializing in American art. Cooks is one of several scholars on the advisory board who offered feedback on the exhibition led by Denise Murrell, The Met’s Merryl H. and James S. Tisch Curator at Large. Cooks also served as a catalog author, contributing an essay detailing the neglected history of Harlem Renaissance exhibitions.

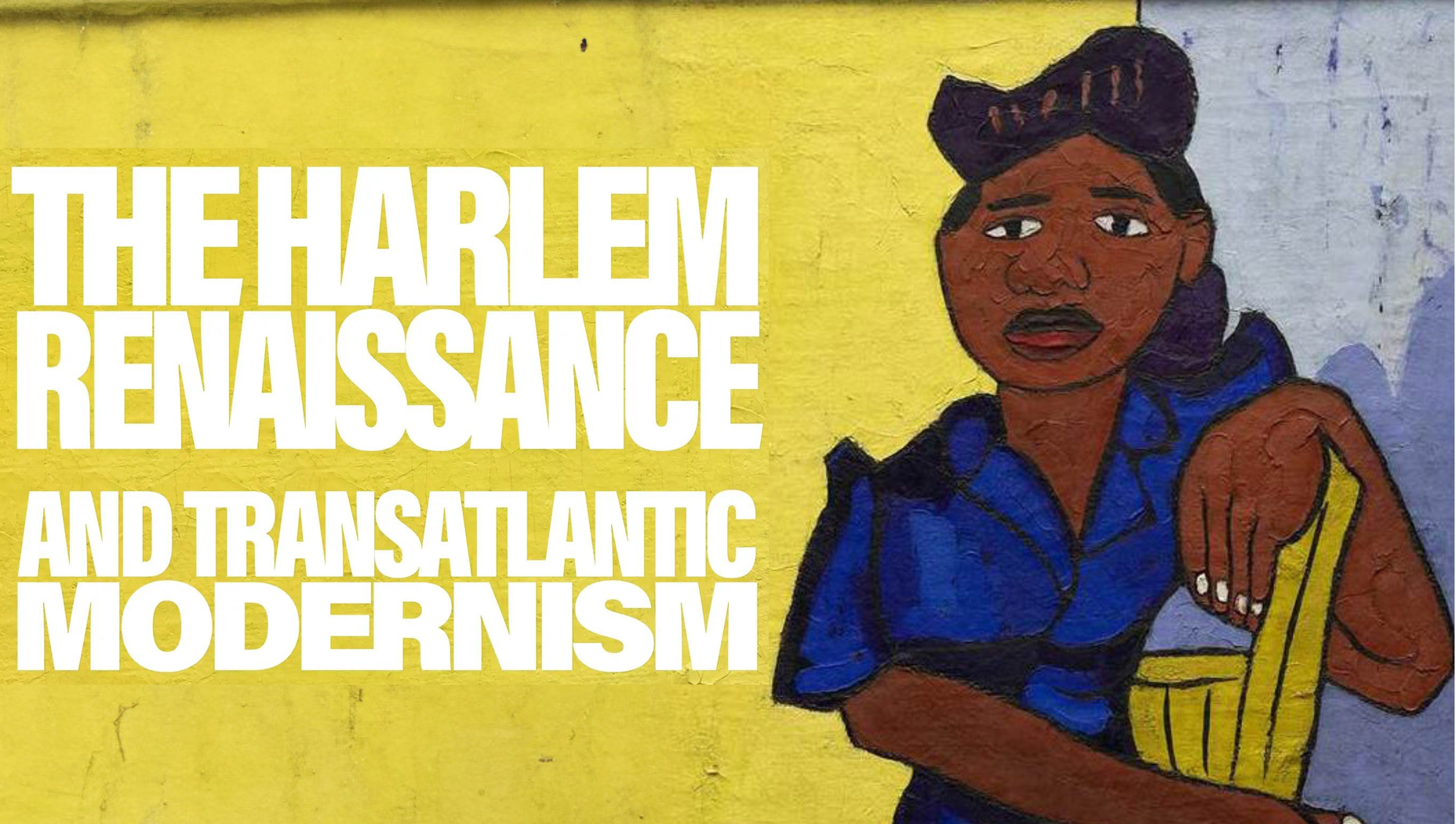

Featuring a diverse array of mediums including painting, sculpture, photography, film, writing and more, the exhibition presents 160 works from well and lesser known Black artists, like Charles Alston, Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage. Murrell collected never-before-exhibited paintings from private family collections and artworks from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) that had been unseen for decades. Together, these pieces display the nuanced ways in which Black artists depicted day-to-day modern life, particularly within the burgeoning Black cities that emerged during the 1920s-40s, and inspired a global renaissance of Black creativity.

“The Harlem Renaissance has been a critical part of my scholarship and teaching throughout my career,” shares Cooks, whose research focuses on African American art, Black visual culture and art world criticism. “Most curators of American art do not learn about the Harlem Renaissance in their academic training. They take that educational gap with them into the museum world and the cycle of omission continues. I was particularly excited to be involved with this long overdue exhibition because it was organized by The Met.”

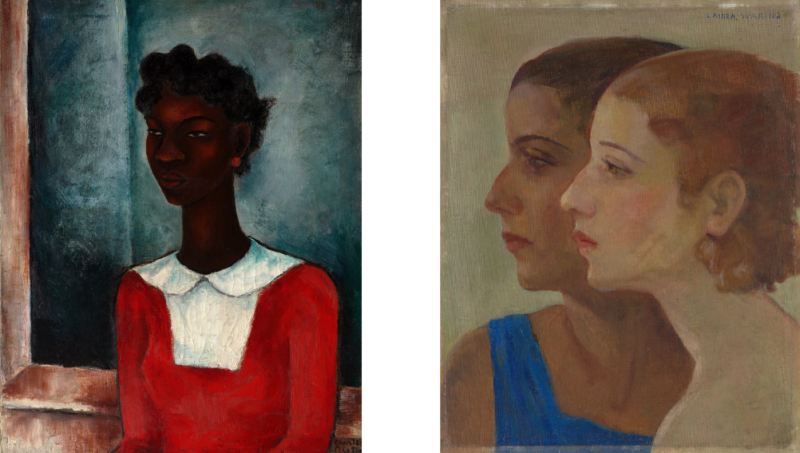

Collection of the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia

Cooks wrote about an earlier exhibition organized by The Met titled “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968” (1969) in her award-winning book, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011). Despite its pivotal role in African American art history, this transformative movement has often been disregarded by prominent museums. As she underscores in her essay for the catalog, hosting the exhibition at The Met holds significant meaning, particularly in light of the institution's overt exclusion of works by Black artists from their "Harlem on My Mind” exhibition.

“‘Harlem on My Mind’ was a controversial exhibition, because it was the first time that The Met had focused its attention on African American people, and its first exhibition that did not include any art,” Cooks explains.

Cooks’ essay examines the historical significance of the Harlem Renaissance, highlighting its emergence as a transformative era for African American creativity. She explores the movement's struggle for recognition within mainstream art institutions, citing pivotal exhibitions like "Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America" (1987) and “I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100” (2018) as crucial steps toward rectifying its omission. Cooks analyzes the impact of these exhibitions, which not only showcased the works of renowned Black artists but also served as platforms for activism, challenging racial disparities in the art world.

A new golden age

Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art

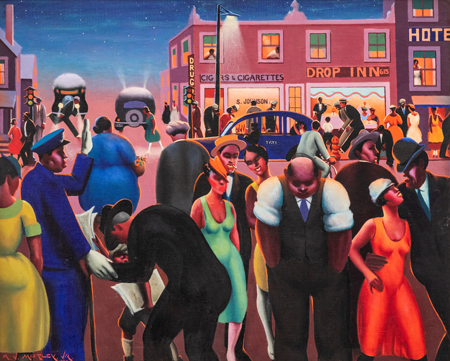

Now known as the Harlem Renaissance, this period of artistic abundance was originally recognized as the New Negro movement. Alain Locke, often referred to as the "dean" of the Harlem Renaissance and editor of the landmark anthology The New Negro, characterized this period as a "spiritual coming of age" that shaped one of the most significant periods of cultural expression in the nation's history. As Black soldiers returned home from World War I, they brought with them a new determination to attain equal civil, social and political rights. It was further bolstered by the rapid expansion of the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans migrated to northern cities like Harlem, New York, to escape racial violence in the Jim Crow South.

The Harlem Renaissance marked the first African-American-led movement of modern arts and literature. Black creatives, through a surge of activity in art, music, dance, literature and philosophy, worked to reshape the portrayal of the modern Black subject and challenge existing racial stereotypes on a global scale. Perhaps most significantly, the Harlem Renaissance supplied African Americans across the United States with a renewed sense of cultural self-determination, racial pride, economic independence and social consciousness. This newfound spirit of empowerment laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement in the coming decades.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

“Because of the contributions that Black people have made to the organizing of the modern world, no account of modern art history is complete without recognizing Black people’s contributions,” Cooks states.

In the early 20th century, she explains, European artists were deeply influenced by African sculpture, sparking a domestic interest in African American art, music and literature in the United States. The artists of the Harlem Renaissance celebrated their heritage and explored themes from West African, Southern and urban traditions in their work. To combat this systematic erasure, The Met’s exhibit juxtaposes works by African American artists with those by European counterparts, highlighting the interconnectedness of artistic developments during this period.

An influential legacy

A century after it began, influential works from the Harlem Renaissance continue to impact the development of art, literature and theater worldwide. Cooks notes the legacy of Pan-African sculptures of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, poetry and novels by Langston Hughes, narrative paintings of Aaron Douglas, Alain Locke’s call for a Black national art, performances of Josephine Baker, the stylistic versatility of William H. Johnson, the soulful portraiture of Laura Wheeler Waring and Palmer Hayden’s satirical compositions. The Harlem Renaissance continues to reverberate in modern culture, acting as a cornerstone for artists, writers and performers who seek to explore and celebrate the intricacies of the African American experience while confronting the pressing issues of our time.

(Right) Laura Wheeler Waring, Mother and Daughter, ca. 1927, Oil on canvas, Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Juan Trujillo

Cooks is currently curating multiple exhibitions, including a future installment at UCI’s Langson Institute and Museum of California Art. She’s also preparing to conduct oral histories of award-winning photographers Coreen Simpson and John Simmons, whose works are represented in the permanent collections of many of the most eminent museums today, as part of the African American Art History Initiative at the Getty Research Institute this winter.

She hopes that a conversation will start about the need for conservation of art from the Harlem Renaissance, leading to an increase in resources to HBCUs that have cared for much of the work. “I hope conversations among curators and donors of American art in museums across the country will encourage them to rethink why their galleries omit the work of Black artists from the Harlem Renaissance. Why, they should ask, don’t we have galleries that reflect the diversity of artists working in the 1920s, ‘30s and beyond?”

She adds, “With each new group exhibition of Harlem Renaissance art, viewers deepen and expand their understanding of the movement. We are still learning things from history that impact our understanding of the past and influence how we think about our contemporary moment.”

To learn more about the exhibition and Cooks’ role, check out this UCI Podcast.

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.