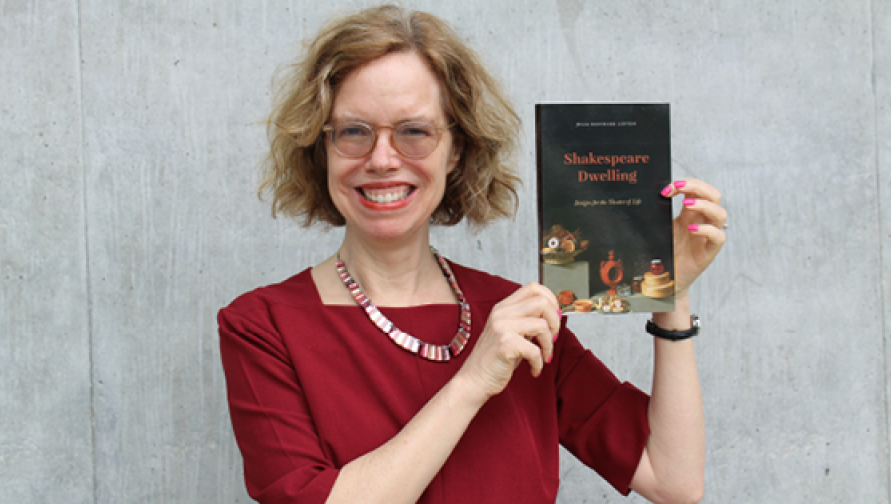

When the character Jacques says “All the world’s a stage” in William Shakespeare’s play “As You Like It,” he is sharing one of Shakespeare’s favorite ideas: actors onstage mirror our unscripted real lives in what can be called the theater of life. Shakespeare’s locales create the spaces where his characters dwell, start and end relationships, and contemplate questions we still grapple with today. This relationship between space and action is the focus of Shakespeare Dwelling: Designs for the Theater of Life (University of Chicago Press, 2018) by Julia Reinhard Lupton, professor of English and co-director of the Shakespeare Center at the University of California, Irvine.

Focusing on five of Shakespeare’s plays (“Romeo and Juliet,” “Macbeth,” “Pericles,” “Cymbeline,” and “The Winter’s Tale”), Lupton creatively draws from Renaissance mores, modern design theory, and the philosophies of Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger to explore how the worlds we live in shape our beliefs, experiences, actions and opportunities. Shakespeare Dwelling synthesizes Lupton’s expertise in design theory and Shakespeare and builds off her previous books Citizen-Saints: Shakespeare and Political Theology and Thinking with Shakespeare: Essays on Politics and Life.

We sat down with Lupton to discuss the main themes of Shakespeare Dwelling and find out how these themes can help us better design our spaces and lives.

Dwelling

“For me, dwelling means living in the world with a sense of attention to one’s environment. Dwelling is the ensemble of rhythms that organize the day into a series of scenes: getting dressed, preparing and sharing food, going to bed and waking up. Each of these scenes choreographs our bodily processes in the spaces we share with other people and in response to their rhythms, their needs. By being aware of this orchestration, we can think about which scenes we’d like to add or cut to better our day-to-day lives.”

Dessert

“We take sweet foods for granted, but it actually took a long time for sweets and savories to play distinctive roles on the European table. Dessert comes from ‘desservi,’ the act of clearing the table. In the seventeenth century, dessert referred not to particular foods so much as to a special moment, when all the dishes were taken away and a fresh start was made. Sometimes guests would move into a separate room or into a garden or pavilion to enjoy sweet cordials and some dried fruit and jellies. Sweet foods are associated in many cultures with divine blessing and a taste of heaven.”

Bedtime rituals

“When I was researching dwelling in ‘Macbeth,’ I got very interested in the history of sleep. (Macbeth kills King Duncan while he is asleep in his bed as Macbeth’s guest.) Macbeth is shocked when he discovers that he cannot say ‘Amen’ to the prayers he hears mumbled on his way back from the killing. In this period, English people had a whole sequence of bedtime prayers at their disposal: there were prayers for lighting candles at sunset, for dressing for bed, and of course for going to sleep. Sleep was – and is – scary: someone could break into your home, or you could die of heart failure, or you could have dreams that will shock you with the intensity of your own worst fears and desires. So bedtime prayers were a means of managing all of that anxiety, finding names for the fears and asking God for assistance in overcoming them. Most of us don’t think of prayer as a kind of life-hacking tool, but it’s interesting to look at how prayer functioned in the past and see what we can learn from that.”

Stage combat and fight call

“When you see actors wrestling, hitting, or throwing each other across the stage, what you are witnessing is a carefully choreographed dance. It takes extraordinary trust as well as skill to pull off the duel at the end of ‘Hamlet,’ or the skirmish that leaves Mercutio dead in ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ In a pre-performance routine called the fight call, the actors run through all of the fighting scenes in slow motion.

Watching a fight call at UCI, I realized that stage fighting visualizes the taking apart and putting together that animates all sorts of intellectual and creative work, from chemistry to choreography. Cooking from a recipe boosts my speed and confidence on those other evenings when I compose meals directly from the fridge. When I pray with others, light Sabbath candles, or make a Passover seder, I am not replacing everyday experience with something mystical or otherworldly. Instead, I am using ritual to decompose and recompose the blur of normal reality in order to live more fluently. The seven days of creation are neither fact nor fiction. Instead, they are a fight call for the world and a recipe for the creative process. Divide, organize, and assemble; constellate, animate, and populate; rest and repeat.”

---

In the epilogue to Shakespeare Dwelling, Lupton reminds us that the phrase “campus climate” ties the ecology of environment to our possibilities for free speech. As in Shakespeare works, the environment that exists for its characters can limit or afford possibilities (for action, contemplation, etc.). Becoming conscious of the ways spaces shape our possibilities affects everything from how you set up a party to how you organize your classroom.

“Observing actors working together to bring a Shakespeare play to life has taught me a lot about the forms of attention available to us as human beings, but often left dormant or neglected,” says Lupton. “In rehearsal, every moment matters: the actors are always listening, watching, finding a way to tell the story and make it real. And they are always, always, always working in partnership with the other actors on stage. If we can bring more of that cooperative sensibility and creative alertness into our work and family lives, we will be happier people. Theater for me is not about pretending; it’s about trust and listening, risk and courage.”

Shakespeare Dwelling: Designs for the Theaters of Life is available on April 6th. To learn more about Lupton and the UCI Shakespeare Center, please visit: http://bit.ly/UCI-Shakespeare