By Nikki Babri

For nearly a century, gay bars have been a cornerstone of the LGBTQ+ community in the United States, serving as a medium for queer communities, politics and cultures. Lucas Hilderbrand, chair and professor of film and media studies, takes a deep dive into the history of gay bars in his latest book, The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After (Duke University Press, 2023).

More than a place to drink

Hilderbrand's inspiration for writing The Bars Are Ours came from recognizing a gap in the LGBTQ+ historical narrative. This “a-ha moment” led him to embark on a mission to document and understand the vital role bars played in queer communities. While gay bars have long been celebrated as vital community institutions, there was no comprehensive history of them. Hilderbrand's work challenges the notion that gay bars are obsolete, shedding light on their continued relevance and the unique roles they continue to serve in the LGBTQ+ landscape. As Hilderbrand notes on the first page, this book is far from an elegy for a bygone institution.

“The gay bar as an institution has not died, nor have its cultures ended,” he writes. “Gay bars have operated as the most visible institution of LGBTQ+ public life for the better part of a century, from before gay liberation until after gay bars’ reported obsolescence.”

Hilderbrand joined UCI’s faculty in 2007. The Bars Are Ours marks his third monograph, following Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright (Duke University Press, 2009), which earned an honorable mention for the Katherine Singer Kovács Book Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, and Paris Is Burning (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2013), which became a part of the Queer Film Classics series. His research interests include video, documentary, pornography and queer studies. He approaches his work with a historical perspective, employing cultural studies methods to understand the nuanced complexities of culture.

Traversing the U.S.

The result of fifteen years of researching, writing and rethinking, The Bars Are Ours takes readers on a journey through various cities and their respective gay bar scenes. “I always envisioned the book as a national account, and I was committed from the start that it not perpetuate the idea that queer history was only made in New York and San Francisco,” says Hilderbrand. Instead of focusing solely on the traditional epicenters of queer culture, he takes a comprehensive approach, exploring cities and small towns from the Midwest to the coasts. Each city serves as a case study, offering a glimpse into the various subcultures and issues that have been critical in shaping the LGBTQ+ experience in the U.S.

“There were cities that felt inevitable to be in the book (New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Los Angeles), but there were also cities I expected to be present but that didn’t coalesce that way. Other cities emerged as unexpected treasure troves of history: Kansas City, Houston, Denver and Boston,” he reveals. “Effectively, I had a general sense of what issues were important, but I let the archive reveal to me which cities told what stories.”

Historically, gay bars played a central role in helping queer individuals find friends, lovers and a sense of community. For generations, they were more than just bars; they represented a rite of passage. Coming out meant going out, and gay bars provided the space for affirming identities and forging connections with kindred strangers. They also became sites to address critical political issues, from police harassment to sexism and racism, to AIDS and gentrification. Today, while the role of bars in political activism has evolved, they remain important for community bonding and celebration. All bars in general, Hilderbrand notes, play a central role in communities, as an informal public “third place” distinct from the home and the workplace.

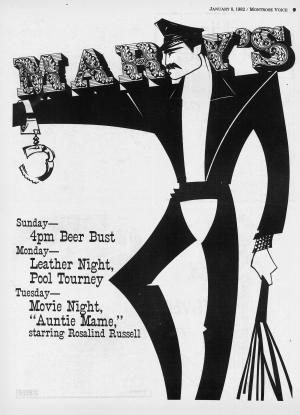

Throughout his research, Hilderbrand uncovered stories and anecdotes that highlight the significance of certain bars or moments in LGBTQ+ history. In the case of Mary's in Houston, it transcended the traditional leather bar archetype to play a pivotal role in local political organizing and the community response to the AIDS epidemic. Notably – and perhaps surprisingly – Houston boasted one of the most effective local gay political caucuses in the nation, wielding unprecedented sway in local elections.

Unearthing hidden histories

The research for the book came with its challenges, primarily the scarcity of documentation regarding bar histories. While archives contained intriguing materials like branded matchbooks and flyers (see: a supplemental gallery of images), they frequently lacked narratives of what actually happened within these spaces. Hilderbrand often relied on the national and local gay press to piece together the narratives and roles these bars played. He also includes archival posters and images, advertisements and photographs throughout the monograph, highlighting their integral role in sustaining this community.

Additionally, he faced difficulties in reconstructing histories of Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ venues, as these venues were less documented and fewer materials were collected in archives. “Queer of color histories were the hardest to reconstruct because of this lack of archival evidence, and my own whiteness meant I had less immediate, lived understanding of these spaces and their conditions – insights that I could use to flesh out histories of white spaces,” he says. “But I was also determined that any history of gay bars had to include histories of Black and Latinx venues.” A former advisee of Hilderbrand, Dan Bustillo (Ph.D. Visual Studies ‘23), whose research focuses on queer and trans Latinx studies, is a named contributor to the book, and collaborated with Hilderbrand on the Los Angeles chapter titled “Donde Todo Es Diferente: Queer Latinx Nightlife in Los Angeles.”

Hilderbrand's hope is that The Bars Are Ours will not only educate readers about the rich history of gay bars but also provide a deep, emotional understanding of these spaces. “It’s equally important that we understand history as not just a series of dates and facts but also as something lived and felt,” he emphasizes. “I hope people sense the full range of human experiences – the wit, the inventiveness, the erotic and the hurt – in these histories.”

The future of nightlife

The Bars Are Ours challenges some common assumptions about LGBTQ+ culture, including Hilderbrand’s own initial knowledge about gay bar culture. For instance, he found that certain aspects, like drag, have unexpectedly recent histories. While many assume that drag has always been a staple of gay bars, his research revealed that before the 1960s, female impersonators performed in nightclubs for primarily straight audiences. While gay men occasionally dressed up in drag, it wasn't until the 1960s and later that drag became a gay bar staple. This shift marked a turning point, and is one of the reasons why Hilderbrand chose to begin his book in 1960.

As for the future of gay nightlife, Hilderbrand acknowledges the shift from specific brick-and-mortar bars to events and parties catering to particular subcommunities. He emphasizes the need to expand the definition of what constitutes a bar and points out that the culture of gay bars and nightlife extends beyond traditional bar settings. It also includes dance clubs, bathhouses and parties, even if they don't strictly adhere to legal definitions of bars.

“What I am curious to see, as more people identify as non-binary, as asexual or as pansexual, is what that means for spaces based upon definitions of gender and sexual orientation,” he shares. “I don’t think we know yet what such nightlife will look like, or if nightlife will even be a framework for these communities.”

Despite a decade-and-a-half of extensive research on LGBTQ+ bars, readers might be surprised to learn that Hilderbrand identifies as an introvert and is usually too bashful to strike up conversations with strangers in a bar. Nevertheless, keep an eye out because he thrives on the dance floor, where he fully lives his best life.