By Megan Cole

In Hollywood’s account of 1960s Los Angeles, it’s summer all the time: The Beach Boys have just released “Surfin’ USA,” palm trees sway gently in the breeze, and the piers are packed with the young, vibrant and carefree. Just a few miles away from this largely white and affluent beach-going crowd, however, the city looks less like paradise and more like a powder keg.

This radical, revolutionary and turbulent side of mid-century Los Angeles takes center-stage in Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (Verso, 2020), a recently released 800-page tour de force co-written by Jon Wiener, professor emeritus of history at UCI and contributing editor at The Nation, and Mike Davis, former professor of history at UCI and acclaimed California historian. While “most histories of L.A. in the sixties have focused on popular music, on Hollywood, on the beach,” says Wiener, “life in the Black and Latino neighborhoods has been neglected — the flatlands where the working-class heroes of our book lived.”

For many, the idea of “California counterculture” might conjure images of Berkeley’s free speech protesters, or the hippies in Haight-Ashbury immortalized by author Joan Didion — not South Central or East L.A. But as Wiener and Davis note, decades of racist and classist policies targeting over a million Angelenos of African, Asian and Mexican descent were approaching a boiling point by 1960, priming L.A.’s working-class neighborhoods for a decade of righteous unrest.

These Angelenos were systematically policed, harassed, arrested, segregated, denied economic opportunity — in short, “edited out of utopia,” assert Wiener and Davis. Though organizers from diverse backgrounds protested for disparate reasons, many were united over their opposition to LAPD violence, the Vietnam draft and racialized poverty, as well as the “issue of issues”: racial segregation and suburbanization. Unlike some histories of the revolutionary ’60s, Set the Night on Fire focuses comprehensively on the relationships, intersections and shared roots between many of these movements, rather than centering any one in isolation.

Tracing this inter-movement solidarity and discovering just how many Angelenos got involved in social justice causes, was a revelation. Most surprising to Wiener was “how young the kids involved in protests were — high school and even junior high school kids by the late sixties.” He adds that, contrary to popular narratives, “the centers of protest were not the big university campuses — it was the state colleges, the community colleges and the high schools.”

Wiener, who has spent his entire career as a historian at UCI, is no stranger to twentieth-century counterculture and political dissent. As a scholar, he specializes in post-World War II U.S. history and society; two of his most popular UCI courses, “American Politics from FDR to Obama” and “Cold War Culture,” inspired some material in Set the Night on Fire. He is perhaps best known for spearheading a successful 25-year legal battle with the FBI over the release of confidential files on John Lennon, and subsequently, for authoring two books on the ex-Beatle. Wiener retired just before the 2016 presidential election, but his engagement with contemporary politics carries on: he currently hosts the podcasts, “Trump Watch” on KFPK and “Start Making Sense,” The Nation’s weekly podcast.

Wiener first moved to L.A. in 1969, just in time to witness the last vestiges of the unrest and rich resistance recorded in the book: a decade of civil rights organizing by Black, Latino and Asian American activists; anti-Vietnam protests; the Watts Uprising (and subsequent “Watts Renaissance”: “a remarkable flowering of jazz, popular music, sculpture and art”); the first gay street demonstration in America; women’s liberation marches; and countless intersections of these all. While the tumultuous decade drew to a close, the activism it catalyzed — and the injustices it brought to light — did not.

Knowing the understudied revolutionary history of L.A. is especially crucial now, Wiener suggests, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement. Many have pointed out similarities between the 1965 Watts Uprising and the current movements surging across Los Angeles and the nation; Wiener notes differences, too, like the fact that “the Black Lives Matter movement today is much better organized than the movements of the sixties — much bigger, much more long-lasting, much more diverse, and has won some significant victories.” According to Wiener, in order to fully comprehend our current situation, we need to study its complicated origins.

“Civil unrest is a well-known feature of American history, from the very beginning, and past episodes suggest what makes for ‘unrest’ and what results it can bring – positive and negative,” Wiener says, adding that future historians shouldn’t strive to simplify the past, but instead attend to its complexities and contradictions. “I know it’s an old-fashioned idea — education not as preparation for a job but as a way to understand things. [But] many of us believe understanding the past provides important insights to our lives today — not just similarities in the past, but the vast differences one finds.”

And the lessons of history may be more relevant now than ever. As John Densmore, drummer for The Doors, told Wiener and Davis in Set the Night on Fire’s epigram, “The seeds of civil rights and the peace movement and feminism were planted in the sixties. And they are big seeds. Maybe they take fifty or a hundred years to reach fruition. So, stop complaining, and get out your watering can.”

Set the Night on Fire is available for purchase now.

Follow Wiener on Twitter @JonWiener1.

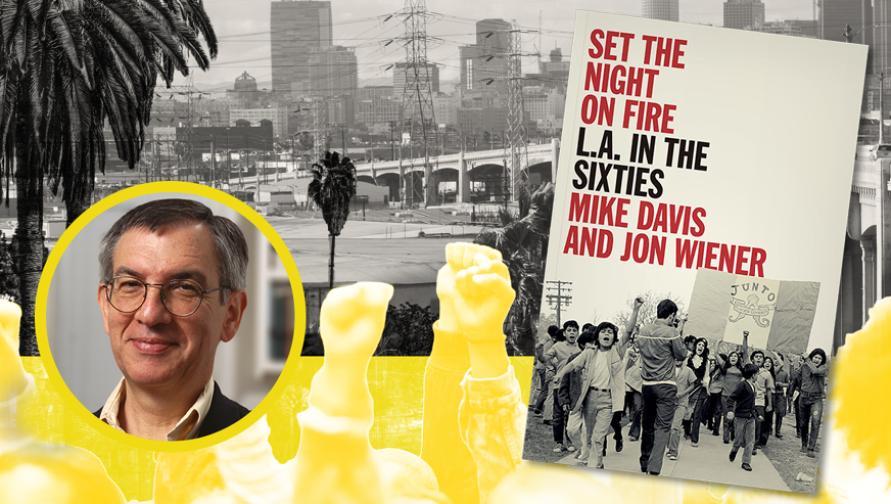

Pictured: Jon Wiener and the cover of Set the Night on Fire.

In Hollywood’s account of 1960s Los Angeles, it’s summer all the time: The Beach Boys have just released “Surfin’ USA,” palm trees sway gently in the breeze, and the piers are packed with the young, vibrant and carefree. Just a few miles away from this largely white and affluent beach-going crowd, however, the city looks less like paradise and more like a powder keg.

This radical, revolutionary and turbulent side of mid-century Los Angeles takes center-stage in Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (Verso, 2020), a recently released 800-page tour de force co-written by Jon Wiener, professor emeritus of history at UCI and contributing editor at The Nation, and Mike Davis, former professor of history at UCI and acclaimed California historian. While “most histories of L.A. in the sixties have focused on popular music, on Hollywood, on the beach,” says Wiener, “life in the Black and Latino neighborhoods has been neglected — the flatlands where the working-class heroes of our book lived.”

For many, the idea of “California counterculture” might conjure images of Berkeley’s free speech protesters, or the hippies in Haight-Ashbury immortalized by author Joan Didion — not South Central or East L.A. But as Wiener and Davis note, decades of racist and classist policies targeting over a million Angelenos of African, Asian and Mexican descent were approaching a boiling point by 1960, priming L.A.’s working-class neighborhoods for a decade of righteous unrest.

These Angelenos were systematically policed, harassed, arrested, segregated, denied economic opportunity — in short, “edited out of utopia,” assert Wiener and Davis. Though organizers from diverse backgrounds protested for disparate reasons, many were united over their opposition to LAPD violence, the Vietnam draft and racialized poverty, as well as the “issue of issues”: racial segregation and suburbanization. Unlike some histories of the revolutionary ’60s, Set the Night on Fire focuses comprehensively on the relationships, intersections and shared roots between many of these movements, rather than centering any one in isolation.

Tracing this inter-movement solidarity and discovering just how many Angelenos got involved in social justice causes, was a revelation. Most surprising to Wiener was “how young the kids involved in protests were — high school and even junior high school kids by the late sixties.” He adds that, contrary to popular narratives, “the centers of protest were not the big university campuses — it was the state colleges, the community colleges and the high schools.”

Wiener, who has spent his entire career as a historian at UCI, is no stranger to twentieth-century counterculture and political dissent. As a scholar, he specializes in post-World War II U.S. history and society; two of his most popular UCI courses, “American Politics from FDR to Obama” and “Cold War Culture,” inspired some material in Set the Night on Fire. He is perhaps best known for spearheading a successful 25-year legal battle with the FBI over the release of confidential files on John Lennon, and subsequently, for authoring two books on the ex-Beatle. Wiener retired just before the 2016 presidential election, but his engagement with contemporary politics carries on: he currently hosts the podcasts, “Trump Watch” on KFPK and “Start Making Sense,” The Nation’s weekly podcast.

Wiener first moved to L.A. in 1969, just in time to witness the last vestiges of the unrest and rich resistance recorded in the book: a decade of civil rights organizing by Black, Latino and Asian American activists; anti-Vietnam protests; the Watts Uprising (and subsequent “Watts Renaissance”: “a remarkable flowering of jazz, popular music, sculpture and art”); the first gay street demonstration in America; women’s liberation marches; and countless intersections of these all. While the tumultuous decade drew to a close, the activism it catalyzed — and the injustices it brought to light — did not.

Knowing the understudied revolutionary history of L.A. is especially crucial now, Wiener suggests, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement. Many have pointed out similarities between the 1965 Watts Uprising and the current movements surging across Los Angeles and the nation; Wiener notes differences, too, like the fact that “the Black Lives Matter movement today is much better organized than the movements of the sixties — much bigger, much more long-lasting, much more diverse, and has won some significant victories.” According to Wiener, in order to fully comprehend our current situation, we need to study its complicated origins.

“Civil unrest is a well-known feature of American history, from the very beginning, and past episodes suggest what makes for ‘unrest’ and what results it can bring – positive and negative,” Wiener says, adding that future historians shouldn’t strive to simplify the past, but instead attend to its complexities and contradictions. “I know it’s an old-fashioned idea — education not as preparation for a job but as a way to understand things. [But] many of us believe understanding the past provides important insights to our lives today — not just similarities in the past, but the vast differences one finds.”

And the lessons of history may be more relevant now than ever. As John Densmore, drummer for The Doors, told Wiener and Davis in Set the Night on Fire’s epigram, “The seeds of civil rights and the peace movement and feminism were planted in the sixties. And they are big seeds. Maybe they take fifty or a hundred years to reach fruition. So, stop complaining, and get out your watering can.”

Set the Night on Fire is available for purchase now.

Follow Wiener on Twitter @JonWiener1.

Pictured: Jon Wiener and the cover of Set the Night on Fire.

History