By Nikki Babri

In 2020, when a Thai celebrity faced attacks from Chinese nationalists over a social media post, something unexpected happened. Thai youth rallied to his defense, sparking broader conversations about authoritarianism and democracy. Within days, activists from Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan had united online under a new banner: the Milk Tea Alliance.

For Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a Distinguished Professor of history at UC Irvine who has been tracking Asian youth movements for decades, this moment marked the beginning of a transnational phenomenon. His latest book, The Milk Tea Alliance: Inside Asia’s Struggle Against Autocracy and Beijing (Columbia Global Reports, 2025), explores how young activists have forged connections across geographical, cultural and linguistic divides in their shared struggle for democracy.

From Hong Kong to a regional movement

Wasserstrom built his career on studying Chinese history and politics with previous books on Shanghai’s past and Hong Kong’s present. He was already following Hong Kong’s protests throughout the mid-2010s when talk of a “Milk Tea Alliance” began appearing online in early 2020.

The alliance takes its name from the dairy-based tea drinks popular across Hong Kong, Thailand and Taiwan – in contrast to mainland China, where tea is traditionally consumed without milk.

What truly fascinated Wasserstrom were the images coming out of Bangkok later that year, showing protesters adopting tactics and chanting anthems he recognized from Hong Kong’s movements. “It felt like a baton had been passed from one part of Asia to another in a pro-democracy relay race,” he explains. When protests erupted in Burma (also known as Myanmar, but Wasserstrom uses Burma for its familiarity to general readers) in early 2021, drawing on the same symbols and strategies used in Hong Kong and Bangkok, the pattern became undeniable.

Three activists, one cause

Wasserstrom’s book centers on three figures: Agnes Chow, a former Hong Kong student leader who co-founded a now-banned political party; Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal, a Thai activist known for protesting compulsory military service; and Ye Myint Win (known internationally as Nickey Diamond), a human rights activist who fled Burma for Germany in the early 2020s.

These three represent the diversity of the movement. They practice different religions (Catholicism, Buddhism, Islam) and were living on different continents (in Toronto, Bangkok and Germany when Wasserstrom finished his book), yet share common democratic values and resistance strategies.

Wasserstrom’s research involved extensive travel and creative meeting arrangements. His meeting with Nickey Diamond had a cinematic quality. “The first and only time we spoke face to face was after agreeing to look for each other by a statue on a wharf in a town on a lake near where he is going to graduate school in Europe,” Wasserstrom recalls. “I felt a bit like a character in a spy novel.”

While he met Chow only once in 2018, he spoke extensively with Hong Kong exiles who knew her well, respecting her need to maintain a low profile.

Wasserstrom’s most extensive relationship developed with the Bangkok protagonist in his story – who he refers to as Netiwit, following the Thai convention of primarily using first names in most contexts – through years of exchanges on Signal, a secure messaging app. Wasserstrom had initially traveled to Thailand in 2022 hoping to meet Netiwit, only to learn he had become a monk and wasn’t seeing visitors.

They eventually met in 2024 after the activist had shed his monk’s robes specifically to challenge Thailand’s military enlistment requirement as a conscientious objector rather than remain exempt on religious grounds. Their first face-to-face meeting came at Bangkok’s Delicious Democracy Café – which instantly became Wasserstrom’s favorite place in the city. What began as research interviews evolved into long conversations about books and ideas. They’ve continued these discussions into 2025, with Netiwit now doing graduate work at Harvard Divinity School, and he and Wasserstrom participating in academic panels together on the East Coast.

Different struggles, shared strategies

The three settings Wasserstrom explores represent vastly different political realities. Hong Kong imprisoned hundreds of political dissidents after Beijing imposed a national security law in 2020. Thailand uses the military to undermine democratic elections while criminalizing criticism of its royal family. Burma descended into civil war after a 2021 military coup, resulting in thousands of deaths and millions displaced.

Yet activists in these countries feel deeply connected. Online and in the streets, they express solidarity, share information and exchange resources across borders. “The primary goal of Milk Tea Alliance activists is to see their communities governed in a more just and democratic fashion,” Wasserstrom writes. “They champion fundamental rights such as free elections, free speech, free assembly and civil liberties.”

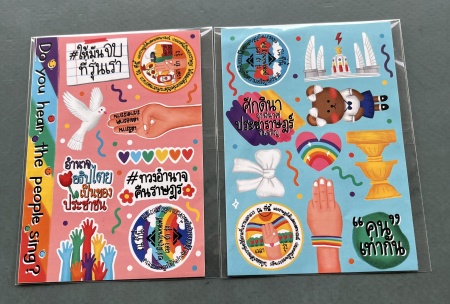

Umbrellas, iconic in Hong Kong’s 2014 and 2019 protests, became central to Bangkok demonstrations in 2020. Burmese protesters’ practice of banging pots spread to Thai demonstrators. Protest songs sung in Thai on one side of the Thailand-Burma border began appearing in Burmese on the other side. Hong Kong activists went so far as to create a crowdsourced Google document summarizing lessons from their 2019 movement and translated it into Burmese for anti-coup activists.

Pop culture as political resistance

One of the most striking aspects of these movements is their sophisticated use of popular culture symbols. Young activists across Asia have deployed an arsenal of symbolic references, from Guy Fawkes masks to songs from Les Misérables (“Do You Hear the People Sing?”), the Harry Potter series to rap music.

The three-finger salute from The Hunger Games has become particularly powerful. First appearing in 2014 and 2015 protests across Hong Kong, Thailand and Burma, it became a defining symbol in Bangkok by the early 2020s. Its most significant impact came in Burma’s resistance struggle, where the gesture now features prominently in street protests and resistance videos. In a memorable act of defiance, Burma’s UN representative displayed the salute during a speech opposing the junta, expressing solidarity with protesters.

“There is a lot that’s new about the specific uses of popular culture by youth activists in Asia recently,” Wasserstrom observes, though he sees echoes in Western movements like women wearing Handmaid’s Tale-inspired clothing to protest abortion restrictions.

And the phenomenon shows no signs of slowing. Even as Wasserstrom’s book went to press, South Korean protests against martial law in late 2024 displayed similar characteristics, with young people using popular culture symbols and women playing central roles. Netiwit posted messages of solidarity that welcomed Seoul’s youth as honorary Milk Tea Alliance members. More recently, upheavals in Nepal and Madagascar, in which the dominant pop culture symbol has become a pirate flag from a popular manga and anime series, have shown similar patterns of youth-led resistance, suggesting the contagion of democratic aspirations continues to spread across Asia and beyond.

Looking ahead

Wasserstrom’s work continues to expand in new directions. Taiwanese publisher Acropolis will soon release a Chinese language edition of The Milk Tea Alliance – his second book to be translated into Chinese. Additionally, a short primer on China under Xi Jinping titled Everything You Wanted to Know About China* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) will be published in February 2026.

His next book project explores George Orwell’s connections to Asia. Returning to one of The Milk Tea Alliance’s settings, Wasserstrom examines how Orwell’s experience as a colonial police officer in Burma shaped his understanding of authoritarian power. Dystopian fiction makes another appearance: while Hunger Games symbolism appears in recent protests, Orwell’s works surfaced in earlier demonstrations. In 2014, Hong Kong students quoted Animal Farm on protest banners, while Thai students responded to a junta-blocked screening of Nineteen Eighty-Four by holding copies on street corners, implying that Thailand had become a Big Brother state. “I’ve written in the past about the way it does and doesn’t make sense to think of China as an ‘Orwellian’ place,” Wasserstrom explains, “so there’s a return to even earlier work in this project.”

Whether future historians will remember this as the “Milk Tea Alliance era” or see the events in Wasserstrom’s book as laying the groundwork for movements yet to come remains uncertain. What emerges clearly from his research is that despite overwhelming odds, with opponents better funded and armed, the activists’ optimism has proven to be infectious.

“By highlighting the courage and resolve of just a few alliance members,” Wasserstrom reflects, “I am left with a profound sense of hope – that a new generation has risen to confront the region’s drift toward authoritarianism. These activists deeply believe in the possibility of a better future even in dark times, and it is their collective courage that sustains this vision.”

On October 20, 2025, join Wasserstrom as he discusses The Milk Tea Alliance at “The Art of the Interview and the Craft of the Profile” event hosted by the UCI Forum for the Academy.

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.