By Nikki Babri

Fifty years after the Vietnam War’s end, the children and grandchildren of Vietnamese refugees fill UC Irvine lecture halls, many carrying questions about family histories they’ve only heard in pieces.

It's a generational divide that Assistant Professor of History Diu-Huong Nguyen encounters regularly. Students spend hours in her office, trying to piece together the painful experiences that brought their families to Orange County. They can chat with their grandparents about dinner plans in Vietnamese, but asking about wartime trauma? That’s much harder.

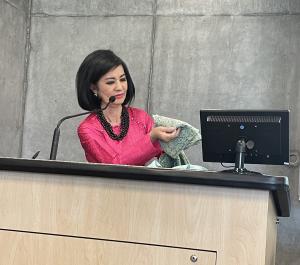

“2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and of the foundation of the Vietnamese American community in the U.S. and particularly Orange County, which is home to the largest Vietnamese community outside Vietnam,” explains Professor Nguyen.

Commemorating through community stories

To mark this milestone, she organized a three-day event series featuring speakers across generations – many sharing their stories publicly for the first time – coming together to share deeply personal journeys of surviving war and building community in Orange County. “Voices from Viet Nam to America” opened with a symposium featuring a former U.S. Ambassador who witnessed the war’s final days alongside panels of community members who lived through the war in Vietnam and shaped the creation of Little Saigon from the ground up.

The second day featured a curated music production and concert titled "From Vietnam to America – The Odyssey & Beyond," which included a forty-minute musical production that reinterpreted the harrowing journey of Vietnamese “boat people” using Vietnamese traditional instruments that mimicked the sounds of refugee boats and ocean waves. The event series concluded with a screening of Elizabeth Ai’s documentary New Wave, which explored how 1980s punk music became an unlikely sanctuary for Vietnamese American teenagers trying to figure out their own identities while carrying the weight of their parents’ unspoken traumas.

Orange County’s transformation

Orange County entered the story in April 1975, when the fall of Saigon triggered the first wave of Vietnamese refugees fleeing to the United States. Many early refugees were processed at Camp Pendleton – the first Vietnamese refugee camp in the U.S. – before settling throughout Southern California.

This initial wave was only the beginning. Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, a second wave of refugees arrived, fleeing by boat or foot through Cambodia and Thailand. These “boat people” often spent months in refugee camps before resettling in the U.S. A third wave followed through the 1980s and 1990s via structured programs like the UN’s Orderly Departure Program, which was designed to reunite families separated by war.

Professor Nguyen’s symposium highlighted contributions from community builders and multigenerational stories. Linh Kochan, with her mother and siblings, fled Vietnam by boat in 1980 after her father’s imprisonment in a reeducation camp. They lived in refugee camps before eventually reuniting with him in Southern California in 1989. Now a UCI alumna and co-president of the Vietnamese American Alumni Chapter, she has dedicated herself to preserving these stories.

“Our family has been involved in many events and projects to preserve the personal stories of those whose lives mirror the history of Vietnam – before, during and after the Vietnam War,” Kochan explains. “These stories help give voice to those who perished or are too pained to speak, and also send the message that the human spirit is strong and can overcome unimaginable travesties.”

For many refugees, the choice to settle in Orange County wasn’t arbitrary. The region’s subtropical climate reminded many of them of South Vietnam, and by the 1980s, word-of-mouth networks drew Vietnamese families to areas where friends and relatives had already established roots. They transformed former strawberry fields and orange groves in Westminster and Garden Grove into a vibrant commercial and cultural center known as Little Saigon.

Building university and community connections

As Orange County’s Vietnamese American community grew, UCI became more than just the local university. For families still figuring out life in America, it offered something precious: accessible higher education close to home.

When Professor Nguyen teaches her history class on the Vietnam Wars, she begins by highlighting the longstanding connection between UCI and the Vietnamese community. “I always show my students pictures of the UCI campus back in 1969 when they had the anti-war movement right here on campus,” she explains. The black-and-white images show protesters gathered outside the Langson Library, just four years after UCI’s founding.

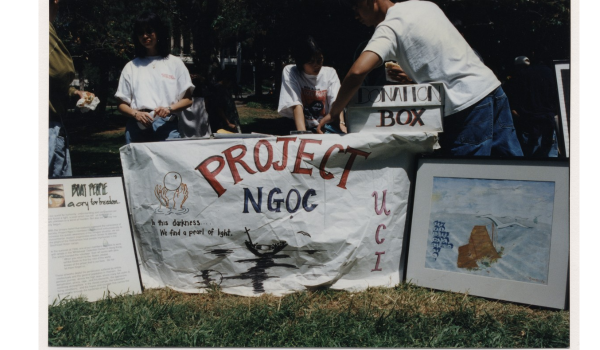

By the 1980s, Vietnamese American students weren’t just attending UCI – they were actively helping their community domestically and abroad. Project Ngoc, a student-led humanitarian organization created in 1987, exemplified this engagement. The self-funded project sent UCI volunteers to refugee camps in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia to teach English and provide support to those still awaiting resettlement.

Though Project Ngoc disbanded in 1997 after most refugees had been resettled, its collection remains in UCI’s Southeast Asian Archive and this spirit of community engagement continues. The “Viet Stories: Vietnamese American Oral History Project,” launched in 2011 by Professor Emerita Linda Vo, has assembled over a decade’s worth of life stories from Southern California’s Vietnamese American community.

More recently, Professor Nguyen currently leads the “My Viet Nam Story: Oral History Project,” which began in 2021 and utilizes student interviewers to capture eyewitness testimonies from those who lived through the war. “As I work with individuals of the Vietnam War generation in Orange County, all of them in their 80s and 90s, we find ourselves in a race against time to capture, document and preserve their invaluable experiences and perspectives,” she shares. “In doing this oral history project at UCI, we strive to bring history closer to the public to ensure the lessons, struggles and human stories of the Vietnam War are not forgotten, but rather continue to inform and educate generations to come.”

A new generation’s perspective

The Vietnamese American presence at UCI continues evolving with each generation. Students like Brian Nguyen, a senior majoring in English and political science, represent a new wave of Vietnamese American scholars engaging with their community’s history. As a UTeacher, Brian Nguyen developed and taught his own course titled “Vietnam War Stories,” examining how the conflict has been remembered across different communities and mediums.

“I think my generation of Vietnamese American students brings a unique kind of critical distance to the Vietnam War and its histories,” he shares. “We’re far enough removed that we’re not beholden to a single dominant narrative, but close enough that the war still shapes our family histories and our identities.”

This generational shift extends to questions of place and belonging. “The older generation tends to be more nostalgic for a version of Vietnam that’s been lost,” Brian Nguyen observes. “But for those of us born in the U.S., the stakes often feel different. We’re more invested in places like Little Saigon – not as echoes of a homeland, but as spaces where something new and distinctly Vietnamese American is being made.”

Preserving language across continents

Frances Nguyen still remembers what she was wearing when she fled Vietnam on April 29, 1975: a flowery top and pants along with her Catholic school uniform shirt embroidered with “RP” (Regina Pacis, meaning “Queen of Peace” in Latin). Five decades later, as a Westminster School District Board member and former Chamber of Commerce president, she helped establish the nation’s first Vietnamese-English dual language immersion program.

“We left our homeland in 1975 and brought with us our history and heritage,” she explains. “We need to give young Vietnamese people a ‘tool’ to be proud of their Vietnamese heritage. This tool is the Vietnamese language, history and cultural values.” The pre-K-12 program, which integrates native Vietnamese and English-speaking students in the classroom, has demonstrated remarkable success, with participating students achieving higher academic performance than their peers.

This demand for Vietnamese language education extends to UCI, where the program has served nearly 5,000 students since fall 2000.

Professor of English Jerry Won Lee, who directs the Program in Global Languages & Cultures, isn’t shocked by the numbers. “Vietnamese is easily the most popular language offered through the World Language Programs. This comes as little surprise considering the high number of UCI students who are heritage speakers of Vietnamese.”

These heritage speakers – often second- or third-generation Vietnamese Americans whose grandparents were war refugees – typically have conversational abilities but lack formal instruction in reading and writing. Now there’s a growing desire among students to strengthen those cultural and linguistic connections beyond just casual communication.

Continuing the conversation

For Professor Nguyen, the commemorative event series represented more than historical reflection. When speakers courageously shared stories despite personal trauma, and when audiences listened with openness, real learning happened. “I’ve found it’s important for UCI to host events like this 50th anniversary series because it provides valuable opportunities for meaningful intergenerational exchange and cultural understanding,” she reflects.

The university setting itself carries special significance for Vietnamese families. As Frances Nguyen notes, “Vietnamese people value education and respect educational leaders, so having a symposium at a university sends a message to Vietnamese people that the information discussed is ‘true’ information.” With few universities teaching Vietnamese studies, she adds, younger generations often struggle to learn about their roots beyond what family members can share.

This generational gap is something Professor Nguyen sees reflected in her own students – those born after the war but who still carry inherited trauma from their families. “By showcasing stories of the past 50 years, I hope that participants can gain a deeper understanding of how the war in Vietnam has impacted individuals, families and communities long after the conflict ends. As we highlight the significant contributions of Vietnamese Americans to our broader society, I also hope this dialogue helps preserve the Vietnamese heritage, foster greater empathy for immigrant communities and strengthen community bonds across generations”

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.