By Nikki Babri

Comics are a powerful medium for cultural expression and social commentary, blending art and literature to explore complex ideas beyond the reach of traditional text. Breaking new ground in this evolving field is Rocío Pichon-Rivière, UC Irvine assistant professor of Spanish and Portuguese.

Pichon-Rivière’s scholarship explores the many facets of Latinx comics, which gained prominence in the late 20th century as a unique voice for Hispanic and Latino experiences in the United States. As founding co-director of the UCI Graphic Narratives Research Cluster and a board member of the Graphic Medicine International Collective (GMIC), she examines the intersection of visual narratives, cultural identity and social issues, bringing attention to the often-overlooked stories of Latinx communities and their representation in graphic literature.

The art of visual storytelling

Pichon-Rivière’s journey into the world of comics began in her native Argentina. “I grew up reading Mafalda – a famous and fantastic comic strip by Quino that was, to me, an education in political thinking and in drawing with simple lines,” she recalls. This exposure to comics as a medium for social commentary was further cemented at age nine when she was given a copy of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in Spanish translation.

Despite the mature themes present, comics were still largely perceived as children’s literature. Her review of Maus from the viewpoint of a child became her first publication. She began drawing silent scenes in comics aesthetics but only recently began to thread stories and arguments within them.

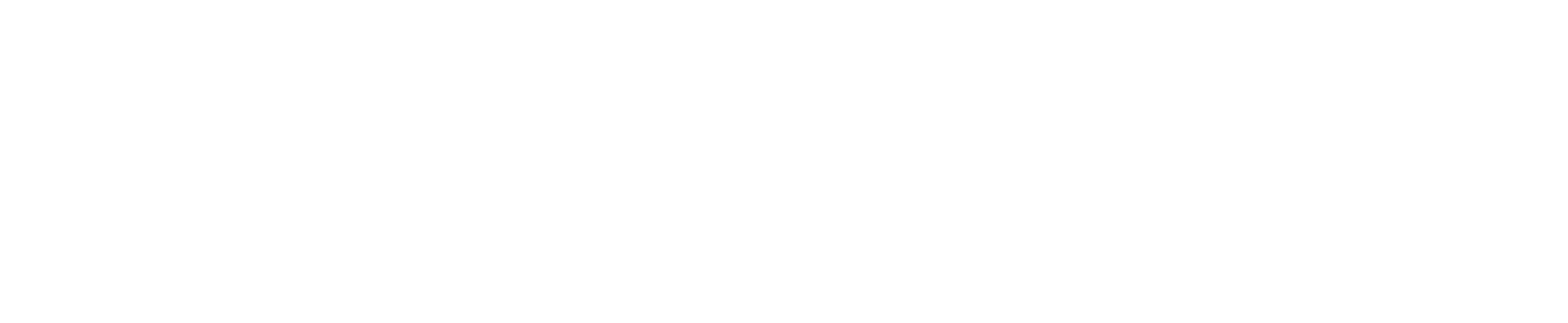

“As a visual storyteller, I am fascinated by the ways in which images can elicit reading experiences that are non-verbal,” Pichon-Rivière explains. “My drawings play between literal representation and metaphor. I like figuration without realism, where the deviation from likeness is in the service of non-verbal thinking: to show not how things look but how they can feel in the silence between the lines.”

Reflecting her academic interests, Pichon-Rivière’s comics interweave character narratives with broader political and social themes. Her work approaches the visualization of injustice with sensitivity, using minimalist techniques and embracing the power of silence and blank space to convey complex ideas without overwhelming or traumatizing the reader.

Breaking language barriers

Pichon-Rivière views Latinx comics, which encompass works from Latin America and U.S. Latinx authors, as a powerful medium for political expression. Comics scholars, who define comics as graphic narratives or sequential art, trace its roots to pre-colonial Indigenous graphic narratives in Abya Yala (the Indigenous name for the Americas).

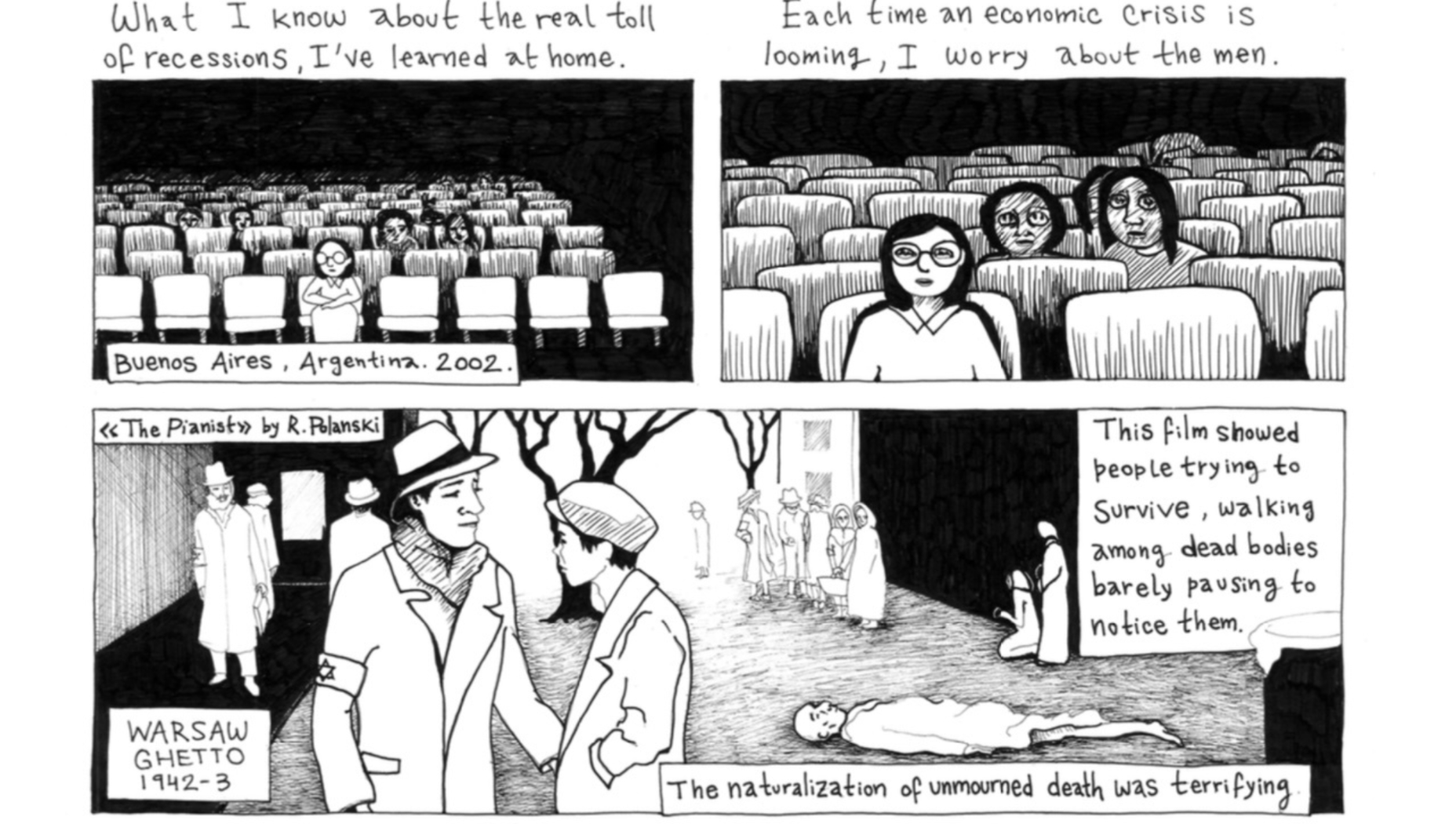

Contemporary Latinx comics often draw inspiration from these ancient visual traditions, which were used to document history before and after European colonization. Pichon-Rivière points to Duncan Tonatiuh’s Undocumented: A Workers Fight as a prime example of this influence. “The book’s accordion-style format mimics Mesoamerican codices, which reads as a commentary on the experiences of Indigenous undocumented immigrants and their belonging to Abya Yala from a time before these national borders even existed.”

“Because of their visuality, comics transcend the borders established by language,” Pichon-Rivière says. This visual language surpasses linguistic, national and temporal boundaries, offering a form of communication that connects diverse audiences and cultures – Latinx and otherwise.

The bilingual and timeless nature of many Latinx comics makes them particularly effective in bridging cultural and generational gaps within Latinx communities, where language differences can be significant. “Comics, as they rely so heavily on non-verbal cues, become a resting ground for linguistic code-switching,” explains Pichon-Rivière. “Many Latinx comics switch between Spanish and English and the visuals provide continuity and context for those who are reading a language with which they might not feel entirely comfortable.”

Comics as a tool for healing

Her work with comics has also led her to explore unexpected intersections between visual storytelling and public health. As a board member of the GMIC, she advocates for the field of graphic medicine, which brings together healthcare professionals, patients and academics to explore health issues through comics.

Pichon-Rivière aims to increase Latinx representation in graphic medicine, recognizing the unique ability of comics to visualize the intricate relationship between mind and body. She explores drawing as a healing tool, demonstrating how it can aid in processing the psychological aspects of illness and reconfiguring one’s sense of embodiment. “There is a distinction between healing and cure. Whether there is a cure or not, the arts have been proven helpful to process meaning and to regain a sense of wholeness.” This approach offers a non-verbal medium for expressing complex health-related experiences, providing a connection between traditional medical discourse and the lived experiences of illness.

This healing approach is exemplified in her published comic “The Neurobiology of Protest,” which explores the physical, mental and political health impacts of the 2001 economic crisis in Argentina. “Protest can be a healthy and healing response to injustice because the stress response is soothed by the presence of community,” she explains. “But, left to suffer alone, a bodymind with unattended chronic stress can develop all kinds of physical and mental symptoms.”

Pichon-Rivière emphasizes the “bodymind” concept in health humanities and disability studies, which views physical and mental health as interconnected. Comics uniquely explore this interconnectedness through their combination of verbal and non-verbal elements, allowing for a holistic representation of embodiment and character interactions.

Creating community

At UCI, Pichon-Rivière teaches Latinx American Comix, a course where students explore comics in both Spanish and English from various Latinx diasporic communities. She finds the diverse reactions of her students particularly rewarding, noting how different comics resonate with students from various backgrounds.

“Comics offer a way to engage with and visually analyze cultural and social issues that resonate with students,” she says. “My students are often surprised to discover the depth and breadth of Latinx comics, and how they relate to their own experiences or those of their communities, whether they are Latinx or not.”

These classes often spark rich discussions on complex societal issues, from women’s bodies to queer and transgender identities. These topics, she explains, are vital for students who are coming-of-age in times of simultaneous progress and backlash regarding gender and sexuality.

Beyond the classroom, Pichon-Rivière co-directs the UCI Graphic Narratives Research Cluster alongside Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature David Colmenares. The cluster hosts monthly reading groups, plans colloquiums and offers workshops. In spring 2025, they are preparing a colloquium on Latinx Comics and Decolonial/Anti-Colonial visual thinking. Pichon-Rivière is also collaborating on a series of graphic medicine events with Professor Juliet McMullin, who directs the Medical Humanities and Arts Program at UCI School of Medicine.

The future of Latinx comics

Looking to the future, Pichon-Rivière is optimistic about the evolution of Latinx comics. “The field of Latinx comics studies is very young,” she notes, with pioneering scholars like Frederick Luis Aldama, Juan Poblete and Ana Merino still actively teaching. As a new generation of scholars emerges, they are engaging in dialogue with these foundational voices, while simultaneously responding to evolving trends in comics production.

She has observed a move away from traditional visual styles, whether the comics strip cartoons or the realism of the 20th century noir comics, toward more experimental aesthetics that reflect the diverse Latinx experiences and their historical and social contexts. She is excited to see how this shift will open up new possibilities for political thinking and cultural expression within the medium of comics.

As she continues her work, Pichon-Rivière remains committed to fostering community engagement around Latinx comics. “I’m interested not just in studying comics, but in bringing people together to read, create and discuss them,” she emphasizes. To become more involved and learn about upcoming events, she encourages students to join the UCI Graphic Narratives Research Cluster and follow their Instagram.

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.