From mentee to mentor

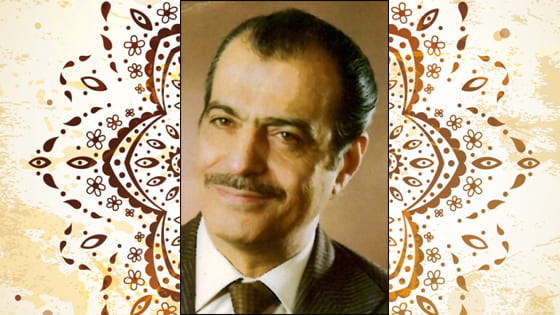

Having been where they are now, history professor David Igler has a lasting influence on first-generation students

Entering a university as a first-generation student can be intimidating, especially when it seems as if faculty are light-years ahead in terms of education and experience.

But the reality is that some professors were once first-generation undergrads themselves. That’s why UCI history professor David Igler always introduces himself to new students as first-generation and encourages them to talk with him during office hours or before or after class.

He was raised in Northern California – “in the shadow of Stanford University” – but his parents never attended college, so his home life was nonacademic. Unlike his peers who were groomed for higher education since they were children, Igler didn’t consider it until midway through high school.

While his parents were emotionally supportive of his decision to go to college, they were unable to help in more tangible ways. He had to rely on mentors at his high school to assist in the application process and write letters of recommendation.

Navigating a new world

Wanting to get as far away from the familiar as possible, Igler enrolled at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Upon his arrival, though, imposter syndrome – the fear of being a “fraud” or undeserving of one’s accomplishments – set in, a common phenomenon among first-generation students.

Determined to succeed anyway, Igler began visiting his professors during office hours on a regular basis from day one. This was a coping mechanism that would stick with him for the rest of his education.

An American studies major, Igler was inspired by an African American studies professor to think about becoming a professor himself. But the journey was daunting; he didn’t believe he was sufficiently intellectual; and the imposter syndrome only intensified in graduate school. Mentoring, however, once again proved instrumental, and Igler overcame his self-doubt to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in just five years.

“One’s success at college usually comes down to putting in the long hours and picking the right path,” he says. “I had some incredible advisers – professors who not only turned me on to the world of ideas, but also modeled what an academic career could look like. It was their example that inspired me to continue my education, so I came back to California and got my Ph.D. in history at UC Berkeley in 1996.”

UCI – where Igler has been teaching since 2004 – offers similar support. “I’m very fortunate to have landed here,” he says. “It’s not like that at every college.”

Paying it forward

A published author and an expert on the history of the Pacific Ocean Basin, the American West, California and the environment, Igler is part of the campus’s First-Generation Faculty Initiative. Established in 2014, it trains relatable instructors to welcome, assist, encourage, inform and advocate for first-gen students – who account for about 60 percent of UCI undergraduates.

“They need to know that some of their professors are not from a long line of professional ancestors,” he says. “In fact, many of us went through a similar process of finding our way through the college experience.”

One of Igler’s mentees is Stephanie Narrow, who was the first in her family to earn a four-year degree and is currently pursuing a doctorate in history at UCI. “It’s easy to feel insignificant in a large research university,” she says. “And it can be much more overwhelming for first-gen students.”

Igler is a source of both unflagging encouragement and practical support, Narrow says, passing on internship and professional opportunities, helping her handle the logistics of attending conferences, and arranging introductions to other senior scholars in her field.

“Sometimes we forget that those we look up to – our mentors, professors, advisers – are human beings who have gone through the same struggles we’re currently dealing with,” she adds. “David’s confidence in my abilities helps me believe in myself during those hopeless, melancholy moments that all of us face.”