COVID-19 Passover Seder

Philosophy graduate student, Rena Goldstein, shares how she spent Seder this Passover, asking "Why is this night different from all other nights?"

My family gatherings occur at different times of the year from what is normative in the U.S. We meet on Rosh Hashana (in the Fall) and Passover (in the Spring), as opposed to Christmas and Easter....

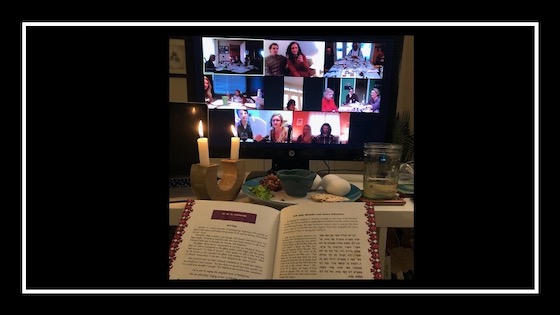

Photo taken by Silvi Goldstein.

For those who don’t know, Passover is the time when Jewish people reflect on the suffering of our people--we recall the exodus of the Jews from slavery in Egypt. The first night of Passover is marked by a Seder, a ritual feast involving storytelling, singing, drinking wine, eating symbolic food (like dipping bitter herbs in saltwater to represent the bitter tears our ancestors shed) and praying. Some Seders stick to the story as it was written in the Torah (Hebrew Bible). Others modernize their Seders, expanding the theme broadly toward social justice issues by reflecting not just on the suffering of the Jewish people, but on the suffering of people from other cultures as well.

Whether the Seder is traditional or modern, for every family, everywhere, we do one thing: we refrain from eating leavened bread. We also ask, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” The first night of Passover reminds us that when the Jewish people left Egypt, they had to do so in a hurry. They could take only what they could carry on their backs; they did not have time to leaven bread.

“Why is this night different from all other nights?” That question holds a duel meaning in 2020. This Passover is different from other Passovers. My family could not travel to be together. We will not share the food our great-great-grandmothers made. We will not go together to pray at Temple. We are sequestered in our homes, either alone or with 2-3 members of our family. We had to adjust to a new sort of living quickly, without time to prepare. We are exiled from our everyday life.

That’s what makes this Passover so different from other Passovers and 2020 so different from all other years. We are having to adjust, to make do with less, to sacrifice seeing our loved ones. Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer once said, “To overcome difficulties is to experience the full delight of existence.” I’m not so sure that’s true—maybe in hindsight?

But I do think that life is never all of something or another. Even when the Jews had to flee Egypt, perhaps they felt grateful to be with their closest kin, to no longer be enslaved. Who knows? One bright spot in all the upheaval of this year is that I was able to spend Passover with more friends and family than usual. We had 25 people from all across the country Zoom together for a potluck Seder. The software was updated, a waiting room enabled, and a meeting password prevented our Seder from being hacked. It was a four-hour meal, with lots of wine, and a hodge-podge of symbolic food (I’ve never before had the responsibility to shop for the Passover Seder, so it did not occur to me to buy all the ingredients ahead of time). We laughed, we sang songs, and for one night we felt relaxed and happy to be together, even though we were apart.