A revolution of words

UCI scholar Frank B. Wilderson puts Afropessimism on the map

By Lisa Fung

It’s hard to think of Frank B. Wilderson III as a revolutionary. But the bearded, bespectacled man with softly graying hair is just that. In his gentle baritone, he shares memories of growing up in 1960s Minneapolis in a predominantly white neighborhood under the watchful eye of his academic parents.

“They did not want me to be a discredit to my race, so I couldn’t dance or sing in talent shows,” he says. “I had to memorize poems, which were sometimes three pages long, and recite from memory Kipling’s ‘Gunga Din’ or Alfred Noyes’ ‘The Highwayman’ to show how intelligent I was.”

He laughs quietly as he recalls memories of his parents preparing to attend a cocktail party but not before leaving a stack of books on Black history for him to study in the living room with one of his sisters. In the morning they would be quizzed, he says, to make sure “we did not look at the TV the night before.”

That obedient young boy would later face the wrath of nuns at his Catholic school in Chicago for refusing to say the Pledge of Allegiance. He would get kicked out of Dartmouth in 1978, just three classes shy of graduation, for organizing a dining hall protest over the treatment of blue-collar Appalachian workers on campus. By the ’90s, he would be one of two Americans elected to the African National Congress in South Africa and would serve as a member of Nelson Mandela’s paramilitary guerilla group, seeking to end apartheid.

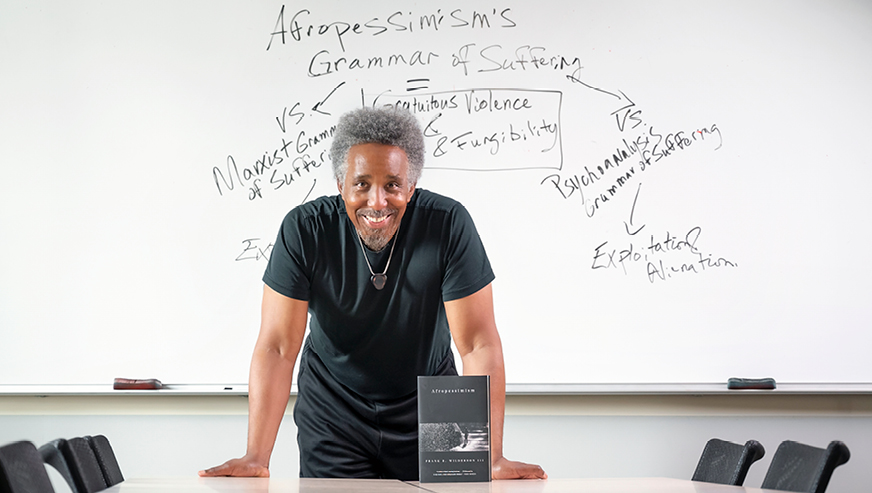

These days, the soft-spoken 64-year-old Wilderson is leading a revolution in words more than actions, through his teaching in the Department of African American Studies at the University of California, Irvine where he serves as chair. He is the author of two acclaimed books and, recently, produced the documentary “Reparations…Now.” His latest book, Afropessimism, will be released on April 7 by Liveright, a W.W. Norton imprint.

“The most transformative period of my life was the summer of 1968 on sabbatical in Seattle and the summer of ’69 through the fall of ’70 when we went to Detroit, Chicago and Berkeley,” says Wilderson, who joined the UCI faculty in 2005. “What I was seeing was that outside of Minneapolis, the world in general and the Black community in particular was in revolt. And I did not have to feel ashamed for my feelings that I felt in this cloistered community. In fact, I was developing an analysis.”

In his new book, Wilderson revisits portions of his unconventional path to academia and Irvine, including a chapter about his suspension from Dartmouth and his return two years later. “It was fortuitous,” he says in an interview, “because the writer Ishmael Reed was there as a visiting faculty member, and he discovered me as a fiction writer and published my first short story.”

With degree in hand, Wilderson returned to Minneapolis and by day worked as a stockbroker – the first Black stockbroker in the state – while teaching and attending classes at the venerable Loft Literary Center and working for the Mozambican Liberation Support Committee at night. This went on for eight years. “I just had two different identities then,” he says. “Then I couldn’t really take it anymore. My sales were always boom and bust. I didn’t have a consistent pattern of working because the only thing I was interested in was writing.”

His passion for words led him to New York City to study creative writing at Columbia. While pursuing his M.F.A., he traveled to South Africa with the intention of writing a novel. There, he met a woman whom he would later marry and became involved in politics at night while teaching at various colleges and universities during the day and working as a dramaturg at the renowned Market Theatre in Johannesburg. Wilderson quickly rose through the ranks of the ANC before having a falling-out with Mandela, who, he says, “comes out of our struggle then moves over to the side to be an accommodationist.” After his marriage broke up, Wilderson returned to the states eventually landing at UC Berkeley to work toward a doctorate in rhetoric and film studies. There he met UCI professor of African American studies Jared Sexton, then a graduate student, Saidiya Hartman, now a professor at Columbia and a 2019 MacArthur fellow, and David Marriott, now a professor of African American studies and philosophy at Penn State, who shared his curiosity about long-held notions of slavery and Blackness.

Together, they gave birth to Afropessimism, a discipline of critical theory that questions the meaning of ‘Blackness’ and posits that the common structures held in Marxism (worker and capitalist), post-colonialism (occupied and occupier), psychoanalytical feminism (woman and man) and other critical theories are unable to explain Black suffering. Expanding on ideas expressed by Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson in his 1982 book Slavery and Social Death, they argue that for Blacks, slavery is an inseparable element of their structural position.

“What we discovered was that the concept of hegemony and the concept of contingent violence do not apply to Black people,” Wilderson says. “That was the major breakthrough, and that’s why it’s getting so much traction.”

Aspects of Afropessimism already existed in Black poetry, Black literature and Black speeches, Wilderson says, “but they were always there in an apologetic and insecure way. All that stuff was there. But it wasn’t Afropessimism.”

Afropessimism is Wilderson’s third book. His first, Incognegro: A Memoir of Exile and Apartheid, is a memoir that weaves together early recollections, poetry and journal entries from his time in South Africa, while his second book, Red, White & Black, deals more with critical theory, examining films and related critical discourse. What makes Afropessimism unique is its blend of critical theory with narrative storytelling, which makes his complex ideas more digestible to a non-academic public.

“What I can do is make people laugh and cry, which is not how an academic journal works,” he says, noting that by chapter five of the book he switches to critical theory. “The storytelling doesn’t leave but by then you’re already in, hooked. That’s what good storytelling is all about. It makes the process of reading pleasurable even though the reader might be uncomfortable as they are reading it. And that’s OK with me.”

After the 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., and the increased political activism of the Black Lives Matter movement, Afropessimism began to gain even more traction, in part, Wilderson says, because “whenever Black people in the street move up and start resisting, what we find is the institutional memory of what we’ve gone through becomes deeper inside the consciousness of Black kids.”

Wilderson is regularly called by Black Lives Matter activists and others from across the globe to lead workshops on Afropessimism. “I spend a good percent of my time doing what would be called promotional work—like John the Baptist,” he says, laughing.

He pauses as his wife, the poet and writer Anita Wilkins, calls out to him from another room.

“My wife says to remind you that I helped to revolutionize African American studies and the Culture & Theory Doctoral Program at UCI,” Wilderson says, first laughing before acknowledging that he and Sexton have helped to put UCI on the map with their work, which has helped attract noted scholars to the Department of African American Studies. “We are just filling up the internet with people who are rethinking how thought is thought, through Afropessimism,” he says. “The world sees UCI as the kind of locus of Afropessimism.”

As he anxiously awaits the release of his book at a time when the coronavirus has shut down most of the country, Wilderson ponders what’s next. He has three unfinished novels – maybe it’s time to return to them. Or setting aside more time for his poetry.

“I never thought I would be like my dad, an academic. I didn’t want to come here; I’m not a huge fan of Orange County. But I lucked out. I like the school tremendously,” he says. “What I’m trying to do – and this book is helping me – is learn how to say I’m a writer. I hope that as time goes on that when people ask me, I can stop saying I’m a professor, and I can start saying I’m a writer.”

Photo credit: Ebrahim Safi